Şehzade Mosque

| Şehzade Mosque | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°00′49.7″N 28°57′25.8″E / 41.013806°N 28.957167°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Mimar Sinan |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Classical Ottoman |

| Groundbreaking | 1543 |

| Completed | 1548 |

| Specifications | |

| Dome height (outer) | 37 meters (121 ft) |

| Dome dia. (inner) | 19 meters (62 ft) |

| Minaret(s) | 2 |

| Minaret height | 55 meters (180 ft) |

| Materials | cut stone, granite, marble |

The Şehzade Mosque (Turkish: Şehzade Camii, from the original Persian شاهزاده Šāhzādeh, meaning "prince") is a 16th-century Ottoman imperial mosque located in the district of Fatih, on the third hill of Istanbul, Turkey. It was commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent as a memorial to his son Şehzade Mehmed who died in 1543. It is sometimes referred to as the "Prince's Mosque" in English.[1] The mosque was one of the earliest and most important works of architect Mimar Sinan and is one of the signature works of Classical Ottoman architecture.[2][3]

History

[edit]The construction of the Şehzade Complex (külliye) was ordered by the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent as a memorial to his favorite son Şehzade Mehmed (born 1521) who died in 1543 while returning to Istanbul after a victorious military campaign in Hungary.[4] Mehmed was the eldest son of Suleiman's only legal wife Hürrem Sultan - although not his eldest son - and before his untimely death he was primed to accept the sultanate following Suleiman's reign. Suleiman is said to have personally mourned the death of Mehmed for forty days at his temporary tomb in Istanbul, the site upon which the imperial architect Mimar Sinan would construct a lavish mausoleum to Mehmed as one part of a larger mosque complex dedicated to the princely heir.

The mausoleum of Mehmed was the first element of the complex to be completed, in 1544.[5] The mosque and the rest of the complex were built between 1545 and 1548.[6] The complex was Sinan's first important imperial commission.[7]

The mosque suffered some damage during the June 2016 bombing that occurred on a nearby street. Some of its windows were shattered.[8][9]

Architecture

[edit]Exterior

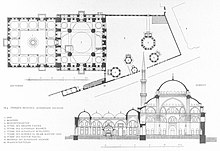

[edit]The mosque is entered through a marble-paved colonnaded forecourt with an area equal to that of the mosque itself.[10] The courtyard is bordered by a portico with five domed bays on each side, with arches in alternating pink and white marble. At the center is an ablution fountain (şadırvan), which was a later donation from Sultan Murat IV.[11]

Sinan added domed porticos along the lateral façades of the building (on the northeast and southwest sides) that help to conceal the supporting buttresses of the structure and to give the exterior a greater sense of monumentality.[12][13]

The twin minarets, attached to the mosque, have two balconies with muqarnas sculpting and interlacing geometric decoration in low relief carved on their shafts. This level of decorative detail on minarets is particular to this mosque and was rarely repeated in later Ottoman mosques.[11] While mosques sponsored by other members of the royal family sometimes had two minarets, the Şehzade Mosque is the only non-sultanic mosque designed by Sinan with two minarets that each had two balconies.[14]

- Exterior of the mosque

-

Main gate to the courtyard

-

The mosque courtyard

-

Entrance to the mosque from the courtyard

-

View of the mosque's northeast side and its external portico

-

View of the mosque's southeast side (behind the mihrab)

-

Details of the minarets

Interior

[edit]

The mosque has a square plan covered by a central dome flanked by four half-domes, with four smaller domes occupying the corners. The central dome is supported by four pillars at its corners. It has a diameter of 19 metres (62 ft) and a height of 37 metres (121 ft).[15]

This design represents the culmination of the previous domed and semi-domed buildings in Ottoman architecture, bringing complete symmetry to the domed designs that earlier Ottoman architects had experimented with.[16] An early version of this design, on a smaller scale, had been used before Sinan in the Fatih Pasha Mosque in Diyarbakır, dated to 1520 or 1523.[17][18]

In addition to the layout's symmetry, Sinan's early innovations are evident in the way he organized the structural supports of the dome. Instead of having the dome rest on thick walls all around it (as was previously common), he concentrated the load-bearing supports into a limited number of buttresses along the outer walls of the mosque and in four pillars inside the mosque itself at the corners of the dome. This allowed for the walls in between the buttresses to be thinner, which in turn allowed for more windows to bring in more light.[12] Sinan also moved the outer walls inward, near the inner edge of the buttresses, so that the buttresses themselves would be less noticeable from the inside (on the outside, he added porticos to conceal them, as mentioned above).[12] The four heavy pillars supporting the dome were a drawback of the design because they distracted from the unity of the space, but Sinan tried to compensate for this by giving them irregular shapes that make them appear less massive.[11]

The painted decoration of the interior is not original and was redone in later periods. Some of these later restorations retained much of the composition of the original classical Ottoman designs while updating them to reflect new techniques adopted under European influence, such as shading.[19] New designs were also added, and among the more classical-like motifs are details that clearly date from the Ottoman Baroque period, although these too have since been repainted and are no longer original.[20][21]

- Interior of the mosque

-

Interior view

-

The main dome

-

Details above the main entrance

-

Detail of one of the main pillars

Legacy and influence

[edit]Sinan considered the Sehzade Mosque his "apprentice" work and was not satisfied with it.[6][22][23] During the rest of his career he did not repeat its layout in any of his other works. He instead experimented with other designs that seemed to aim for a completely unified interior space and for ways to emphasize the visitor's perception of the main dome upon entering a mosque. One of the results of this logic was that any space that did not belong to the central domed space was reduced to a minimum, subordinate role, if not altogether absent.[24]

Despite Sinan's opinion, the symmetrical design of the Şehzade Mosque, with its central dome and four semi-domes, proved popular with later architects in the Ottoman Empire. It was repeated in classical Ottoman mosques built after Sinan, such as the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque, the New Mosque at Eminönü, and the 18th-century reconstruction of the Fatih Mosque.[25][26] It is even found in the 19th-century Mosque of Muhammad Ali in Cairo.[27][28]

Complex

[edit]The other buildings of the Şehzade Mosque complex include a medrese, a tabhane (guesthouse), a caravanserai, an imaret, a small mektep (primary school), and a cemetery with several mausoleums. The mosque and the cemetery are enclosed by a small wall which forms an outer courtyard that also connects to most other elements of the complex.[29]

- Elements of the complex

-

Exterior view of the cemetery and its domed mausoleums

-

Exterior of the madrasa (located on the north side of the complex)

-

Interior of the madrasa

-

Interior courtyard of the imaret (located on the east side of the complex)

-

Interior hall in the imaret

Mausoleums

[edit]There are five mausoleums (türbe) in the funerary garden to the south of the mosque. The earliest and largest is that of Şehzade Mehmed which has a Persian foundation inscription over the entrance with a date of 1543–44.[30] The mausoleum is an octagonal structure, with a fluted dome, polychrome stonework and a triple-arched portico. The interior walls are covered with multi-coloured cuerda seca tiles and the windows have stained glass.[31][a] An unusual feature is the rectangular wooden throne over Mehmed's sarcophagus which symbolized his status as the heir apparent. Within the mausoleum there are also the tombs of Mehmed's daughter Hümaşah Sultan and his youngest brother Şehzade Cihangir (d. 1553). The identity of the fourth sarcophagus in not known.[35]

- Mausoleum of Şehzade Mehmed

-

Exterior of the Mausoleum of Şehzade Mehmed

-

View of the tombs inside the mausoleum

-

View of the tiled walls and the wooden throne above Mehmed's cenotaph

-

View of the dome

-

Detail of the cuerda seca tiles

To the south of the Şehzade mausoleum is the smaller octagonal türbe of Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha, which was also designed by Sinan. The inscription gives the year as AH 968 (1560–61). Rüstem Pasha was the husband of Mihrimah, the daughter of Suleiman the Magnificent. Like the Rüstem Pasha Mosque it is decorated with a large number of underglazed Iznik tiles.[36][37] By the gate to the complex is the türbe of Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha, son-in-law of Murat III, who died in 1603.[38] The türbe was designed by Dalgıç Ahmed Çavuş, and almost equals that of Şehzade Mehmed in design and use of tiled decoration.[39]

- Other mausoleums

-

Mausoleum of Rüstem Pasha

-

Interior of Rüstem Pasha's mausoleum

-

Mausoleum of Ibrahim Pasha

-

Entrance to Ibrahim Pasha's mausoleum

-

Interior of Ibrahim Pasha's mausoleum

Center of Istanbul

[edit]It was said that the "green column" standing at the edge of the cemetery wall of Sehzade complex facing Şehzade Mosque and the street was erected at the location deemed to be the center of Istanbul.[40][41]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Godfrey Goodwin in his book A History of Ottoman Architecture published in 1971 states that the cuerda seca tiles decorating the mausoleum were made in Iznik.[32] From surviving account books the historian Gülru Necipoğlu has shown that the Ottoman court employed a team of tilemakers in Istanbul and it is now generally assumed that all cuerda seca tiles on imperial buildings dating from the first half of the 16th century were manufactured in Istanbul rather than Iznik.[33][34]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Rogers, Sinan, pp. index

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Ottoman". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Kuban 2010, p. 271.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2005, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Kuban 2010, p. 273.

- ^ a b Blair & Bloom 1995, p. 218.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, p. 206.

- ^ "İstanbul'da bombalı saldırı: 7'si polis 11 ölü, 36 yaralı" (in Turkish). Cumhuriyet. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "İstanbul'daki Patlamada Mimar Sinan'ın Şehzade Camii Zarar Gördü". Arkeofili (in Turkish). 7 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2005, p. 196.

- ^ a b c Sumner-Boyd & Freely 2010, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, p. 210.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2005, p. 121.

- ^ Kuban 2010, p. 272.

- ^ Kuban 2010, pp. 258, 271–272.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, pp. 178, 207.

- ^ Kuban 2010, p. 236.

- ^ Bağcı 2002, p. 755.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, p. 268.

- ^ Erçağ, Beyhan (1991). "İstanbul Şehzade Camii Restorasyonu". Vakıf Haftası Dergisi. 8: 213–228.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, p. 207.

- ^ Kuban 2010, pp. 261, 272.

- ^ Kuban 2010, p. 261.

- ^ Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 228–230.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, pp. 340, 345–346, 358, 394, 408.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, p. 408.

- ^ Al-Asad, Mohammad (1992). "The Mosque of Muhammad ʿAli in Cairo". Muqarnas. 9: 39–55. doi:10.2307/1523134. JSTOR 1523134.

- ^ Kuban 2010, pp. 272–275.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2005, p. 193.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2005, p. 198.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, p. 211.

- ^ Necipoğlu 1990.

- ^ Carswell 2006, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2005, p. 200.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2005, p. 327, figs 314-315.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, p. 252.

- ^ Necipoğlu 2005, p. 531, Note 56.

- ^ Sumner-Boyd & Freely 2010, pp. 188–189.

- ^ "İstanbul'un Ortası". Kültür Envanteri. 4 August 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ "Şehzade Mosque and Complex". Historical Marker Database. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bağcı, Serpil (2002). "Painted Decoration in Ottoman Architecture". In Inalcık, Halil; Renda, Günsel (eds.). Ottoman Civilization. Vol. 2. Ankara: Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Culture. pp. 737–759. ISBN 9751730732.

- Blair, Sheila S.; Bloom, Jonathan M. (1995). The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300064650.

- Carswell, John (2006) [1998]. Iznik Pottery. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2441-4.

- Goodwin, Godfrey (1971). A History of Ottoman Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51192-3.

- Kuban, Doğan (2010). Ottoman Architecture. Translated by Mill, Adair. Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 9781851496044.

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (1990). "From International Timurid to Ottoman: a change of taste in sixteenth-century ceramic tiles". Muqarnas. 7: 136–170. doi:10.2307/1523126. JSTOR 1523126.

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-253-9.

- Rüstem, Ünver (2019). Ottoman Baroque: The Architectural Refashioning of Eighteenth-Century Istanbul. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691181875.

- Sumner-Boyd, Hilary; Freely, John (2010). Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (Revised ed.). Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 183–191. ISBN 9780857730053.

Further reading

[edit]- Aptullah Kuran: Sinan: The grand old master of Ottoman architecture, Ada Press Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-941469-00-X (in English)

- Faroqhi, Suraiyah (2005). Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. I B Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-760-2.

- Rogers, J.M. (2007). Sinan: Makers of Islamic Civilization. I B Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-096-3.